Insights & Opinions

Fraud and Scams in 2026: What Benelux Banks Can Learn from The Global State of Scams

Mon, 19 Jan 2026

Online scams are no longer a niche fraud problem sitting at the edge of banking. They’re industrialised, cross-border and increasingly hard for customers (and sometimes even fraud professionals) to spot. That was the central message from Jorij Abraham, Managing Director of the Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA), during our recent The Banking Scene LIVE webinar on the global state of scams, as we kicked off our Q1 2026 research on Fraud and Financial Crime in Benelux Banking.

GASA’s mission is consumer protection, but the implications land heavily on financial services because money movement is where the harm becomes real. Jorij’s take was that scams are old, but the way they scale today is new: remote execution, automation and global rollout have changed the game.

One of the most important framing points Jorij raised at the start of his presentation, is also one of the most uncomfortable: scams are a category of crime where the victim is manipulated into choosing to send money, share data, or grant access. That makes scams both highly effective and heavily underreported.

To keep it simple for consumers, GASA uses a practical “gap” test: if there’s a huge gap between what’s offered and what’s actually delivered, you’re likely dealing with a scam. The formal definition still sits underneath that: “deception for financial gain”, but this consumer-facing framing matters because scammers thrive on ambiguity and plausibility.

And while scamming itself is ancient (Jorij shared an amusing anecdote about “mummified cats” being sold in ancient Egypt, often filled with rubbish rather than actual mummified cats), today’s threat is shaped by scale, speed and realism.

The Scam Economies

Jorij painted a grim global backdrop that should worry European institutions because organised scam capacity doesn’t stay local. He described scam compounds in Southeast Asia, including forced labour dynamics, and noted that even when compounds are raided, enforcement and victim handling constraints make sustained disruption difficult.

Most sobering was the macro point: in some regions, scam/cybercrime activity is becoming embedded in the economy, citing estimates that cybercrime/scams may represent a significant share of GDP in certain countries.

That kind of incentive structure means the supply of scam attempts won’t slow down on its own.

Global patterns and local differences

GASA runs large annual consumer surveys with 46,000 respondents across 42 countries, including nationally representative samples in Belgium and the Netherlands. Those results highlight global commonalities, but also some striking differences between our two neighbouring markets.

One of the more surprising data points: the reported volume of scam messages per person per year differs sharply.

- Belgium: 216 scam encounters per person per year

- Netherlands: 98 scam encounters per person per year

- For contrast, the figure reported for the United States is 377 per person per year

Jorij was open that GASA is still trying to understand the drivers behind the Belgium / Netherlands gap. It could be channel mix, reporting perception, different scammer targeting, or simply different consumer interpretation of what counts as a “scam message”. But regardless of the “why”, the implication is that Belgian consumers appear to face (or at least notice) a much higher level of scam exposure.

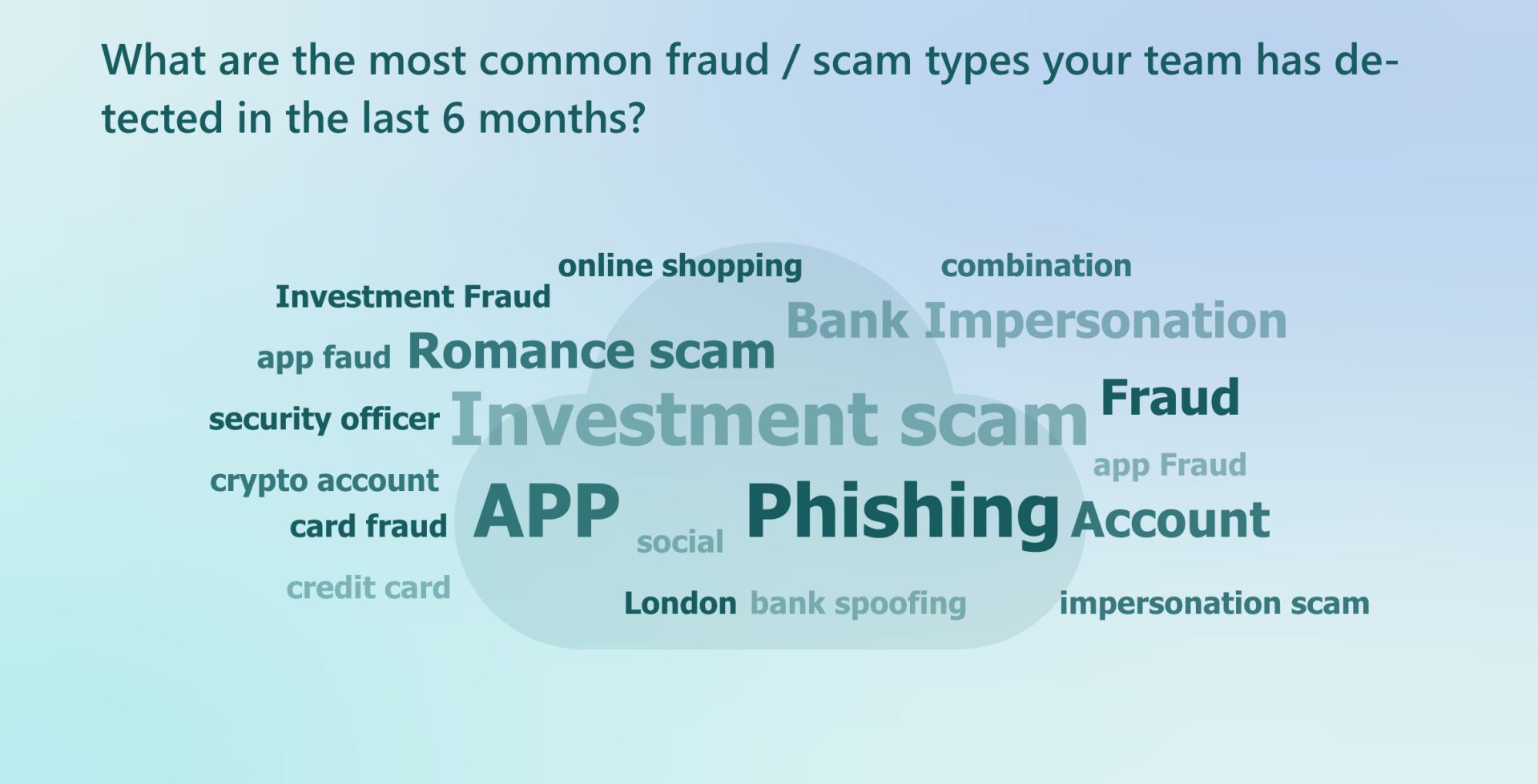

The top scam categories will feel familiar to most fraud and payments teams:

- Online shopping scams (globally and in both Benelux markets)

- Fake invoices (second place in both Belgium and the Netherlands, with only small percentage differences)

- The third spot diverges:

- Netherlands: “unexpected money” style scams e.g., “you won the lottery” type hooks

- Belgium: money recovery scams often targeting people who were already scammed, linked to re-victimisation and, potentially, investment scam prevalence (which was reflected in the "word cloud" responses to our audience poll we ran before Jorij started his presentation).

Another standout statistic: 23% of scam victims in both Belgium and the Netherlands reported actually losing money, which is about the same as the global figure presented in the session, but the average amount lost per scam is very different:

- Belgium: ~€2,000 average loss

- Netherlands: ~€800 average loss

Jorij suggested that this might relate to the mix of scam types, particularly the role of investment scams and follow-on “recovery” scams, but the practical point for Benelux banks is straightforward: Belgian scam losses appear to be materially more severe per incident.

At a global level, GASA estimates total scam losses somewhere between $442bn and $1tn, noting the inherent difficulty in measurement with underreporting, reluctance to disclose amounts, and occasional exaggeration.

Even if you take the conservative end, the numbers are eye-watering!

Globally, a top reason cited for not reporting scams is “I wasn’t sure where to report.” In Belgium and the Netherlands, the more common reason is more damning: people don’t report because they don’t think it will make a difference.

Jorij gave a pragmatic example: if someone loses €30 in an online shopping scam and the counterparty is overseas, the police may be honest that they can’t recover the money. Transparency is good, but it also discourages reporting, which then reduces intelligence, trend visibility, and enforcement prioritisation.

Anyone can get scammed

This isn't just a slogan, it's measurable! A common internal instinct in organisations is to associate scam vulnerability with lack of education or sophistication. GASA’s data pushes back hard on that. Jorij emphasised that scam susceptibility is not neatly tied to education or wealth. Instead, some tendencies increase risk:

- being impulsive or overly optimistic

- being very active online

- being male (slightly higher susceptibility)

- immigrant background (less familiarity with local rules and processes)

- prior victimisation (strong re-targeting effect)

Perhaps most counterintuitive: younger generations and higher-educated groups can be scammed more, potentially because confidence in recognising scams leads to lower vigilance.

And to prove the point in a memorable (and slightly embarrassing) way, GASA has a tradition of scamming its own conference audience: people who work in fraud and cybersecurity!

Jorij described how at the last conference, they used different tactics like fake dinner invitations requiring card details, a “photographer” requesting ID selfies to skip the queue, and a “GASA swag store”, to collect credit cards and identity information from their attendees within minutes.

The lesson: expertise reduces risk, but doesn’t eliminate it, especially under time pressure or social proof.

Instant payments, instant fraud?

After Jorij’s presentation, we moved into Q&A and shifted the discussion from “what’s happening” to “what can we do about it?”

Rik framed a core concern: when instant payments remove the natural cooling-off period, victims don’t get a chance to pause, doubt, and break the spell of urgency, fear or authority bias.

Jorij’s response was pragmatic and slightly provocative: for low-value everyday payments, speed is helpful and scam likelihood is low. But for high-value transfers (think: cars, large invoices, investment transfers), why insist on instant settlement? He argued for tiered friction: deliberate delays, step-up controls, and transaction-context barriers that force time back into the process.

This is especially relevant in the context of APP-style scam dynamics: victims are emotionally “in motion”, and the bank’s window to intervene may be measured in seconds.

Nearly half of our attendees felt that fraud is on the rise post Instant Payments Regulation.

Verification of Payee: useful, but already being gamed

With a few months of mandatory Verification of Payee (VoP) already behind us, we were keen to hear early thoughts from our audience on how it might be impacting fraud. One participant noted VoP can even benefit scammers if they structure fake invoices using a real mule’s name and add “acting on behalf of”, triggering a “green light” match while still diverting funds.

One of our guests shared a particularly relevant Belgian operational concern: with mandatory e-invoicing via the PEPPOL network from 1 January, onboarding and KYC weaknesses in access to invoicing networks could make invoice fraud more scalable, moving from one-off PDF scams to high-volume “legit-looking” system-to-system invoice delivery.

There were also practical, forward-looking ideas on how VoP could evolve beyond a simple “name match”:

- flag whether the account is personal vs corporate

- provide contextual signals such as how old the account is

- detect anomalies using history across payers (e.g., “nine companies pay IBAN X, one suddenly receives IBAN Y”)

Another guest noted that in Belgium, the consumer vs corporate distinction is already in play, and referenced Dutch use of extended fraud risk indicators (eg the FRI by SurePay) as examples of broader signal use.

The broader takeaway is important: no single control “solves” scams. Controls add friction, raise attacker costs, and reduce some losses, but scammers will route around whatever becomes standard.

What GASA thinks will matter most next

Three themes stood out as “next wave” issues:

- Scams becoming unrecognisable

The biggest shift in GASA’s consumer results: people now say they were scammed less because the offer was attractive, and more because it was realistic and believable, a change likely influenced by AI-driven content generation.

- Trust erosion as a societal cost

Jorij shared an example of a lost hiker ignoring calls from rescuers because the number was unknown, suggesting scams are changing how people respond to legitimate outreach.

- “AI to combat AI” is necessary, but not sufficient

The session’s final poll showed strong interest in behavioural biometrics and other AI-enabled defences, but Jorij’s answer to “what one investment would you prioritise?” was essentially: there isn’t one. Scams require layered measures because attackers adapt constantly.

Turning the tide: continuous education plus better signal sharing

GASA’s solution direction is twofold: improve intelligence sharing and keep consumers in a sustained learning loop.

- Global Signal Exchange launched with Google and Oxford Information Labs: now over 32 companies sharing scam indicators (bad sites, emails, phone numbers), reportedly over 1 million signals per day.

- Scam.org planned launch end of February: intended as a global consumer hub to learn, check, report and get support, designed mobile-first and chatbot-oriented.

- Continuous education platform planned around Feb/March 2026: a Duolingo-style, reward-based model to keep scam awareness “sticky”, because one-off campaigns fade in one to two weeks.

For Benelux banks, the practical implication is that consumer protection can’t rely on occasional awareness pushes. It needs ongoing reinforcement, paired with smarter intervention at the point of payment, especially now that instant rails and higher realism compress decision time.

What this means for Benelux banking teams

If you take Jorij’s global lens and apply it locally, a few priorities become hard to ignore:

- Belgium and the Netherlands may look similar in scam prevalence, but average losses and reported exposure differ materially, so national strategies should not be copy-paste.

- Instant payments increase the need for risk-based friction that respects emotional manipulation as a threat vector.

- VoP/name matching is valuable, but without richer context like account age, entity type, behavioural anomaly signals, it risks becoming a false comfort.

- Data sharing and privacy concerns are real, but operational hesitation can become a gift to scammers. Building “safe harbour” approaches and clear rules of engagement is becoming a strategic necessity.

Scams aren’t going away. But the combination of better intelligence exchange, continuous consumer education, and payment-journey controls designed for real human behaviour, not idealised rational behaviour, gives Benelux banks a fighting chance to reduce harm, even as scammers keep adapting.

The Banking Scene: Director's Cut

Rik and I discuss a few of the more eye-opening scam statistics with added anecdotes from our own experiences and The Banking Scene events. As always, you can follow along on your favourite podcast channel here, or watch / listen to the episode below (and don't forget to subscribe!).