Insights & Opinions

CBDCs – What are they good for?

Mon, 21 Mar 2022

According to the latest statistics from The Atlantic Council’s CBDC Tracker, 87 countries representing over 90% of global GDP are currently exploring, or have launched, a CBDC (Central Bank Digital Currency). This is a 148% increase over the 35 countries that were exploring CBDC projects in 2020!

But aren’t CBDC’s just another form of “digital money” and isn’t most of the money in the world already in digital form?

What problems do CBDC’s solve and what opportunities do they open for the future?

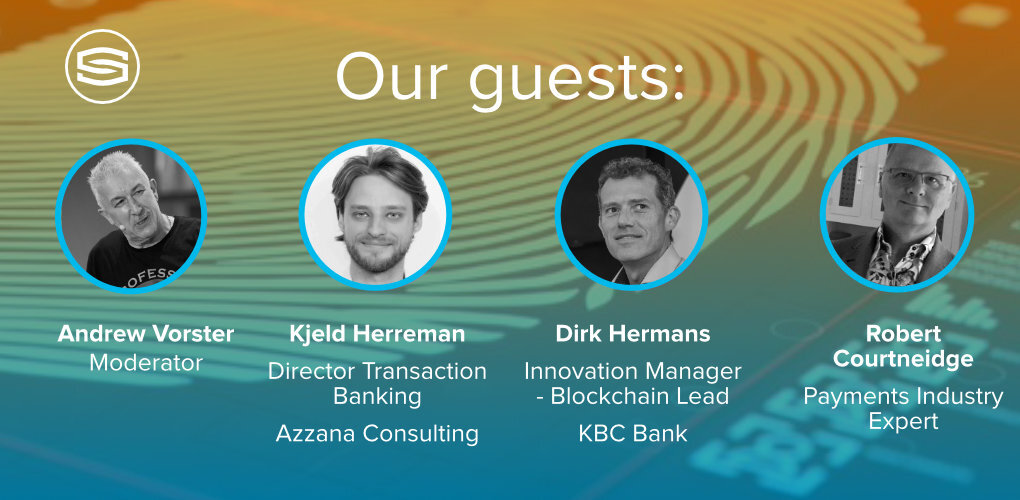

Our guests joining us last week to share their insights and answer our questions were:

- Dirk Hermans, Innovation Manager and Blockchain Lead at KBC

- Kjeld Herreman, Director at Azzana Consulting and

- Robert Courtneidge, Payments Expert & Syndicate Director, The Payments Association

Most of us hold and use very little cash these days as we already have a wide range of ways to transact digitally by way of cards, mobile phones, embedded devices, IoT, online banking or increasingly via one of the over 18,000 cryptocurrencies currently available.

Therefore, the very first point I was looking for clarity on was “what is the fundamental difference between a CBDC and any other forms of digital money we already have?”.

Kjeld explained that in the simplest possible terms, it comes down to liability.

When you open an account at a financial institution, they carry the liability for the transactions you carry out and you need to trust that the institution will keep your money safe until you need to use it. Banks are not required to hold 100% liquidity and it’s by no means impossible for a bank to go bankrupt. Sure, there are different controls and measures in place in different countries across the world but there is always a risk, however small it may be, that you could lose your money.

The same principle also applies to cryptocurrencies. When you transact, the institution that holds your money in digital form (as crypto), is the one that carries the transaction liability. The majority of cryptocurrencies are not regulated in any way and your money is at risk, even with “stablecoins” whose value is tied to a specific fiat currency.

When it comes to a CBDC however, the liability rests with the nation’s monetary authority or Central Bank as it is literally a digital representation of fiat currency.

To think of a CBDC as “digital cash” is therefore not entirely wrong.

It’s not entirely right either as it turns out that CBDCs could potentially open new opportunities.

Robert is the Syndicate Director for a UK consortium that recently published “A New Era for Money” – a green paper co-developed with business leaders from across the financial ecosystem as a call to action for industry stakeholders including businesses, banks, central banks, regulators, government officials and researchers. The paper identifies 4 key use cases for CBDCs, the first of which is retail payments.

This surprised me as we already have so many ways to pay in a retail environment, do we REALLY need another way to pay?

Robert took us back to the pre-smartphone days circa 2007 and asked how many people thought they would NEED an iPhone back then? Most people just didn’t see the point, but as more and more people started using them and the ecosystem started building up around them, they became more and more useful – and who could imagine their life without a smartphone these days?

He believes that CBDCs are a little like that and the real benefit of them won’t come about until more and more people are using them and more and more practical use cases are realised.

“I think the key benefit in retail payments is going to be the programmability of money and I think this is going to be the game-changer”

The aspect of “programmable money” really resonated with Dirk as he and his team have been working on blockchain and smart contracts for over 6 years now.

“The power of a smart contract and the token-based aspect of having the transfer of ownership immediately in a token-based environment, without having a dual accounting system and reconciliation, that to me is the power of programmable money”

Dirk elaborated on this by telling us about KBC’s first case they applied the concept of programmable money to – electric vehicle charging. In this case, the customer deposited money on a collateral account in KBC, which was then converted into tokens on a blockchain. When the customer paid for their charging with the token, the payment was immediately split across all parties that were involved, including the energy provider, the party that delivered the service and the bank. Everything was handled in one go via a smart contract and no reconciliation was required afterwards – a significant change in speed and efficiency of the transactions!

Dirk further opened our eyes to the future possibilities of exchanging digital assets on a token-based platform, which might have sounded like pure science fiction to some of our audience, but they are the potential use cases that he and his team consider would be possible once digital currency use increases.

A member of the audience asked if a CBDC could be programmable, could it possibly be used to stimulate more sustainable or responsible consumption? Wow, interesting question!

The panel responded with several possibilities where for example, paying with a CBDC could automatically trigger a balancing carbon-offset micropayment like a donation to plant a tree. Kjeld also suggested that governments could make conditional payments to citizens for example by providing an energy grant where the CBDCs could only be used to pay energy bills and nothing else.

The conversation took an interesting turn at this point thanks to another question from the audience – “could CBDC increase financial inclusion?”

Almost every single CBDC paper I have read includes something about how issuing the CBDC will increase financial inclusion, but not a single one has explained “how” it would, so I was eager to hear what the panel had to say about the topic.

Dirk was the first to respond with “it depends”. He went on to say that in Belgium, banks are obliged to give everyone access to the free, basic bank account – it’s the law. But this isn’t the same in all countries in the world, therefore in those countries, it would potentially increase financial inclusion as everyone would have access to the CBDC.

But how would everyone have access to a central bank DIGITAL currency?

Robert brought up the one point that has troubled me most when people have talked about CBDCs and Financial Inclusion in the same breath – the issue of digital inclusion.

The general assumption that people (including me until recently) make, is that you need to be digitally included before you can be financially included in a world where physical cash is replaced by a digital representation of cash in the form of a CBDC.

There are millions of people across the world, predominantly from low socio-economic groups, who cannot afford or do not have access to technology for a wide variety of reasons. Any form of money that requires a mobile phone to transact via QR code, SMS, the internet or any other means, automatically excludes these people from the system. While mPesa is often held up as a shining example of success, this overlooks those people that have been totally excluded from the system due to their lack of ability to afford a mobile phone and airtime. Sadly, these same people are also often already the most vulnerable - women, children, refugees and the elderly for example.

Any system predicated on digital inclusion, like Nigeria’s recently launched eNaira which requires a mobile phone number, email address and Bank Verification Number in order to sign up for a wallet, would automatically exclude these groups.

In my personal opinion, this should be a major cause for concern.

But one of the many reasons why I really love The Banking Scene Afterwork sessions is that they force me to challenge my own assumptions and it turns out that my assumption about CBDCs and digital inclusion was in fact entirely incorrect!

Remember what Kjeld said right at the start of the session? The fundamental difference between a CBDC and current forms of “digital money” is the liability.

He did not say anything about form factor, access, technology or anything else for that matter.

And that’s the key.

The eyes of the financial world have been focussed with interest on China’s pilot of the digital Yuan CBDC at the Winter Olympics. While the public adoption of the CBDC might have fallen below their expectations (largely due to the already high availability of convenient payment alternatives), China has demonstrated that mobile phones are not required for a fully functioning CBDC platform.

Prior to the event, the USA officials had encouraged athletes to leave their mobile phones at home in order to limit the possibility for surveillance. This meant that US athletes would potentially be excluded from participating in the CBDC pilot. But China installed ATM style machines and partnered with Visa to produce an instant issue “hardware wallet” in the familiar form of a plastic card. Visitors were able to swap their currency for the equivalent in digital yuan and use the plastic cards within the Olympic village as a means of payment.

Of course, the digital yuan is also available via a mobile phone application that uses QR codes which are far more familiar to the local population, but the key is that mobile phones are not the only form factor. This to me is a far more inclusive approach as it truly does open the system to everyone!

The financial inclusion discussion moved onto the topic of cross border transactions, an area where the panel unanimously believed CBDCs could potentially have a major role to play in increasing speed, reducing costs and improving efficiency overall. A member of the audience from South Africa made a reference to Project Dunbar, which brings together the Reserve Bank of Australia, Central Bank of Malaysia, Monetary Authority of Singapore and South African Reserve Bank with the Bank for International Settlements Innovation Hub to test the use of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) for international settlements.

Dirk mentioned at this time that KBC is a member of Fnality International who are building the foundations and interoperability protocol for a distributed Financial Market Infrastructure (dFMI) to serve the needs of the wholesale banking market.

Our entire discussion up to this point had been focussed on retail CBDC and we hadn’t touched on the difference or the need for wholesale vs retail CBDCs, along with many other questions we simply ran out of time to dive into. Like for example the implications that CBDCs would potentially have on a bank’s balance sheet, or the economy in general for that matter...

I would suggest these topics are probably best covered in multiple future Afterwork sessions as it was clear that while we had learned a lot about CBDCs from our guests, we still had a lot more to learn - be sure to sign up for future sessions!